While there are risk-reducing benefits to expanding central clearing for U.S. Treasurys, experts say that implementing a broader mandate will not be easy and could cause new problems at a time when the market is in a fragile state.

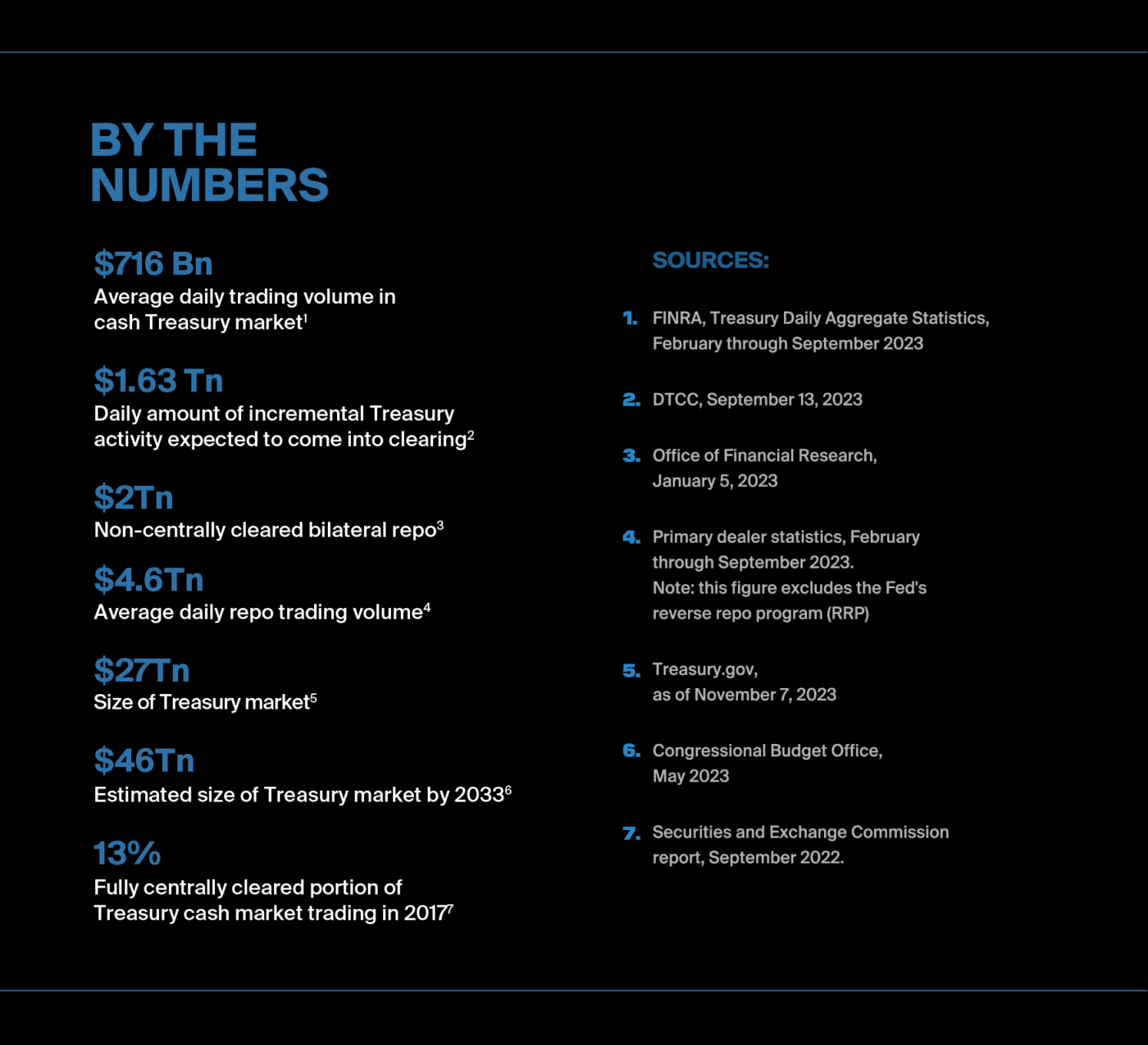

As regulators look to address more frequent turbulence in the $27 trillion U.S. Treasury market with a trade-processing mandate, participants are expecting that the new rule itself could create some waves.

Interest rates are rising, volatility is higher than normal and sudden swings in bond prices have exposed structural weaknesses in the market already. Experts say implementing the new mandate could lead to even more pronounced blips. They also say it could prompt traders to recreate some transactions as futures or other financial arrangements that may be economically similar.

One key rule, which the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) intended to finalize in October and is now expected any day, would require more Treasurys to be routed to a central market utility called a clearinghouse. Proponents believe that this could improve the stability of the market by mitigating the risk of buyers or sellers defaulting between the time of trading and settling. They also think it has the potential to avoid the risk of traders cutting each other off in ways that could cause fire sales and a downward market spiral.

Risk reduction isn’t a given, however. While many experts say that clearing is helpful in preventing defaults from spreading and causing contagion, they also say it is unlikely to stop some stresses from occurring in the first place. Other experts think that central clearing could introduce new dangers, like gaps in liquidity, concentration risks at the clearinghouse, bottlenecks at various access points to the system, or a dash to repaper thousands of legal contracts in a short time frame.

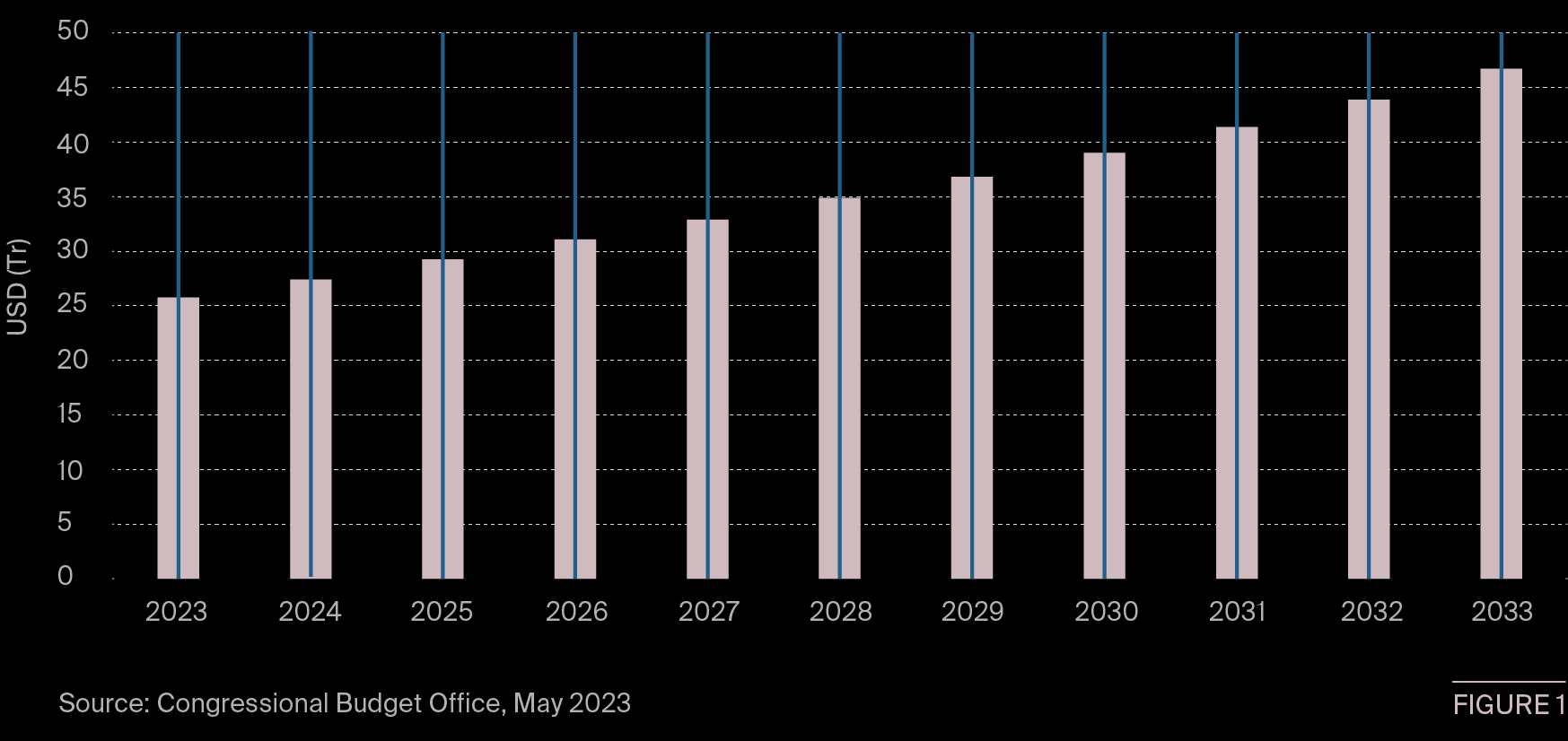

The costs of clearing would have to be borne at a time when the Federal Reserve has been removing stimulus and when the U.S. Treasury has been stepping up its borrowing, these experts say. Those costs may erode the profitability of certain Treasury trades for key market participants, making today’s transaction costs unattractive just when the government needs to stoke investor demand in its new issuance (see Figure 1).

None of these fears has been sufficient to dissuade the Commission, which believes that centralized clearing would make the market safer. But until the details are finalized about which firms and trades are in scope, hundreds of firms will need to prepare to push more than a trillion dollars’ worth of additional Treasury activity into the clearinghouse.

“It’s not only the right thing to do, it’s actually a good time to begin standing this up, given that we’re not in crisis right now,” says Darrell Duffie, professor of finance at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business. “By the time this rule has teeth and is fully implemented, who knows how turbulent the bond market might be?”

Who’s Caught?

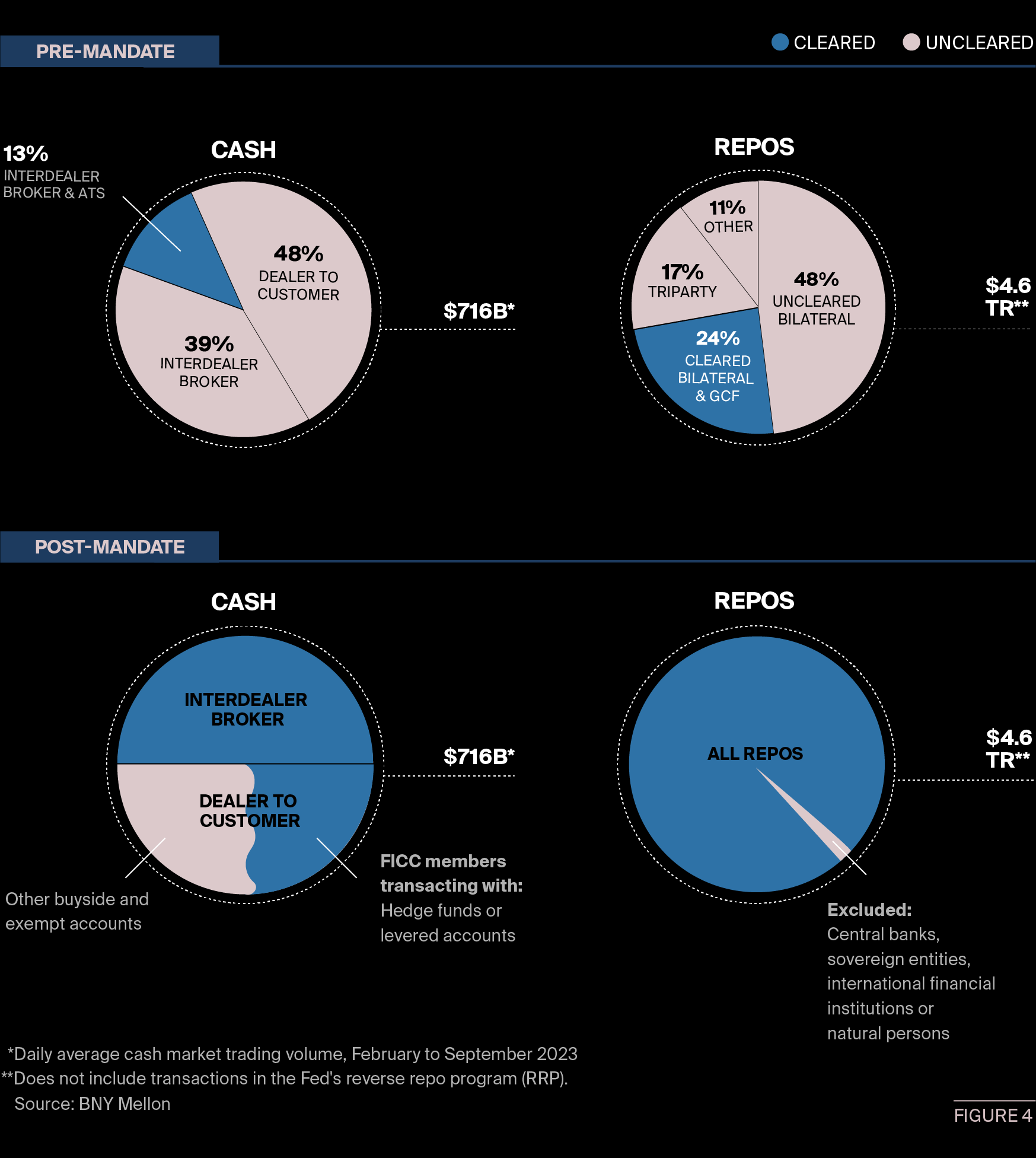

As proposed, the rule would cover most outright Treasury cash trades and all repurchase agreements or “repos” secured on them, with few exceptions. The SEC has indicated that as of 2017, only about 13% of outright Treasurys were fully centrally cleared, and a minority of repos.

The difference between cleared and uncleared trades is important, not just because there is a large slew of trades outside of the clearinghouse, some of which have no margin backstopping them. The gap also means participants cannot benefit from all the clearing efficiencies that they would get if all trades were processed and housed at a single clearing venue.

The Treasury market has always been split in terms of which entities clear and which ones do not, and after the SEC rule is enacted that will continue to be the case. In the future, it is expected that hedge funds that trade with members of the clearinghouse will have to clear, while sovereigns and central banks will not. And in the part of the cash market where bond dealers and so-called “principal trading firms” (PTF) trade among themselves, clearing would be mandated for all players.

Out On Bond

In order to backstop new centrally cleared Treasury trades, dealers would be required to post additional collateral or “margin.” But the SEC has not indicated that it will require dealers to collect a minimum amount of margin from their end-user clients, and today some highly leveraged hedge funds pay close to zero in margin, some experts say. That may change as the market tries to absorb the new costs of clearing and if regulators target such low-margin practices in the future.

The increase in clearing will add significant transparency to the market and shine a brighter light on the Fixed Income Clearing Corp. (FICC), which is part of the Depository Trust & Clearing Corp. (DTCC) and the only approved clearinghouse for Treasurys. The SEC is expected to implement new governance requirements around how FICC evaluates its access models to account for this newly expanded role.

In the future, the FICC would become the counterparty to every centrally cleared trade, and BNY Mellon would continue to be primary settlement agent on most U.S. Treasury transactions. Since the FICC’s settlement is conducted using BNY Mellon, this means that the bank would settle more Treasury trades through the FICC’s account than it does today.

“Central clearing will reassemble the structure of the Treasury market, requiring market participants to reevaluate their trading strategies, find clearing sponsors and optimize their margin and collateral management strategies,” explains Nathaniel Wuerffel, head of market structure at BNY Mellon and the former head of domestic markets at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The SEC could phase in the implementation of the rule, giving participants years to lay new access lines to intermediaries, find the additional capital they need to meet their new commitments, and find support for managing their changing collateral needs. But many market participants are expecting the rule to require a faster implementation timeline, possibly 24 months or less. “There are real systemic benefits, but if the implementation timeline is short, it could be a bumpy transition,” Wuerffel explains.

Pricing Impact

In addition to the fees associated with central clearing, investors may also have to pay more to trade them. The gap between the cost to buy Treasurys and the cost to sell them, known as the bid-offer spread, could widen as the rule is implemented.

Rising costs could encourage traders to pursue other types of financial transactions or those not expected to be in scope, such as open-ended repos that currently cannot be cleared by the FICC, derivatives or other financing arrangements that may mirror repos but have different legal and accounting treatments. Doing so may come with a liquidity tradeoff, however, or additional costs.

Repos Rising

“Market participants will be faced with the choice to withdraw, do synthetic versions of Treasurys or pay up,” says Matthew Daigler, senior counsel at the Managed Funds Association. “The cumulative costs of all these rule proposals are pretty staggering.”

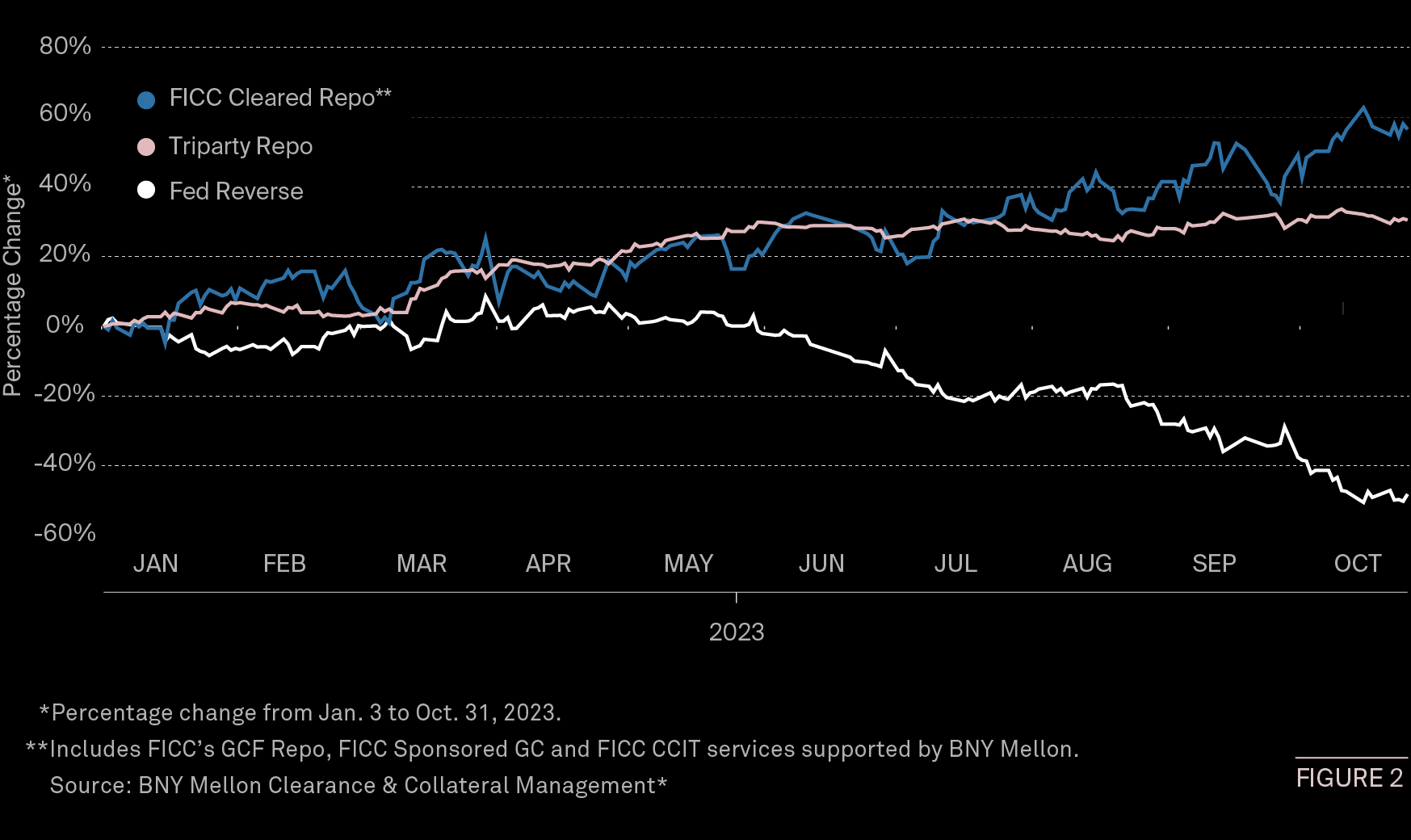

Another additional cost will be signing on with new providers who can facilitate clearing into the FICC. The clearinghouse currently operates three primary access models, but the one that is expected to be the most popular is using a member to sponsor in the trades. The FICC sponsoring program is available for repos and Treasury cash trades and there are around 35 sponsors including BNY Mellon, JPMorgan Chase & Co. and State Street Corp. Balances of cleared sponsored FICC repos have been rising of late, BNY Mellon data show (see Figure 2).

There are real systemic benefits, but if the implementation timeline is short, it could be a bumpy transition.

“We anticipate that sponsored access will grow,” says Laura Klimpel, general manager of the FICC. “We may see certain asset managers that are capable of either using sponsors or establishing captive broker dealers to become direct members of FICC themselves. Some might also route their activity through another one of our indirect access models, called prime broker/ correspondent clearing.”

Currently, some sponsoring members try to recoup their costs by encouraging clients to both execute and clear with them, experts say, and the SEC does not address this in its proposal. But some experts think the bundling effect may come under scrutiny later. “They’re only clearing trades where they’re a counterparty to the trade, rather than clearing all transactions regardless of who executed them,” says Patrick Parkinson, a senior fellow at the Bank Policy Institute.

A Bad Match

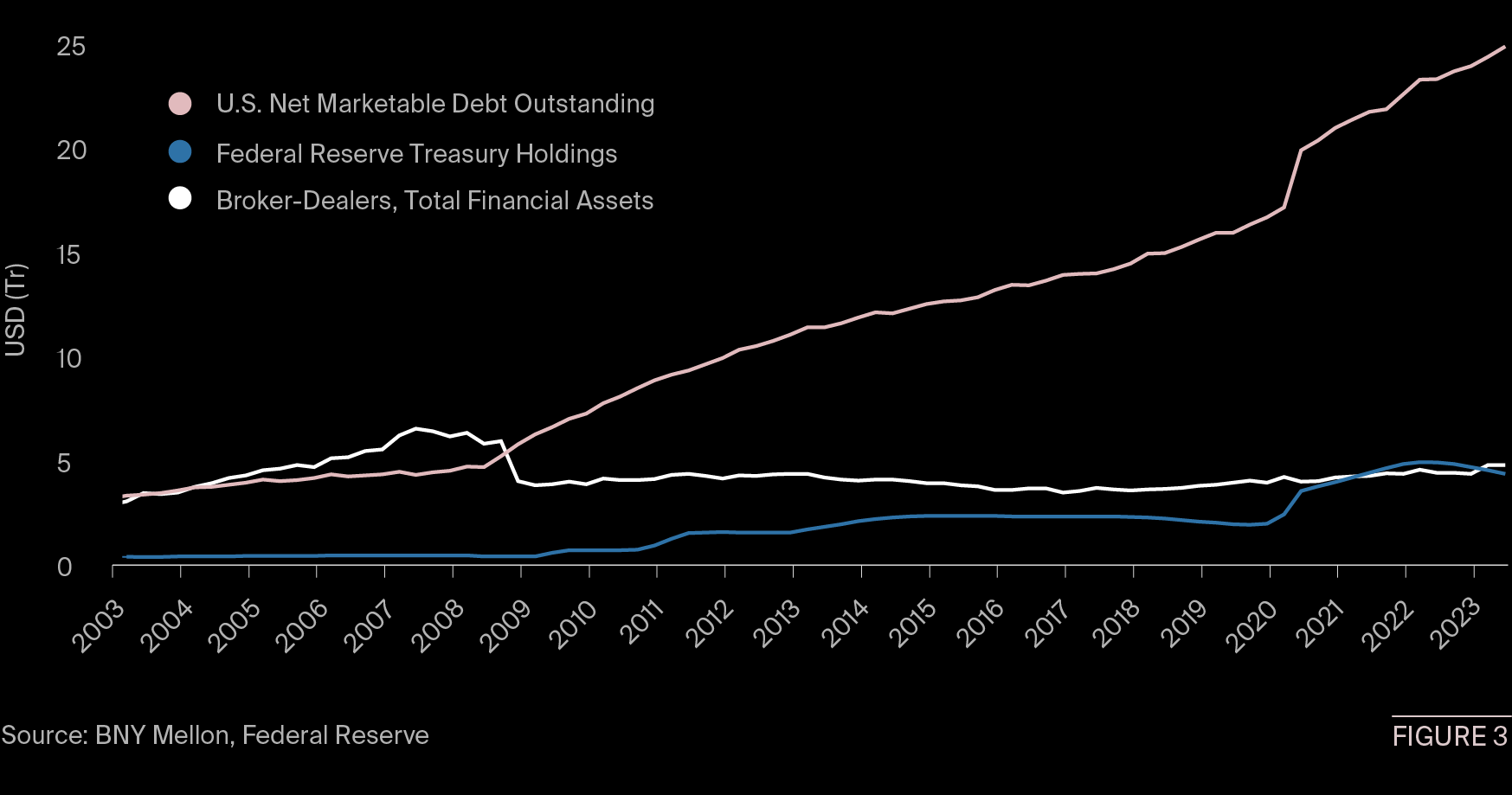

On the one hand, the need to source margin and liquidity are an additional cost associated with more Treasurys being centrally cleared, and who bears that cost is something the industry will have to determine at a challenging time (see Figure 3). On the other hand, clearing has the potential to reduce risks and create some balance sheet savings, potentially lowering bid-ask spreads and yields. That’s because the clearinghouse can “net” down any opposing trades and cancel out those offsetting positions, requiring less margin from members.

A study by the New York Fed in 2021 suggested that central clearing could have lowered dealers’ gross settlement obligations by $800 billion during high-volume trading days.

Package Deal

However it shakes out, it is clear that plugging holes in the Treasury market is time-sensitive work. The amount of Treasury debt outstanding is expected to reach $46 trillion by 2033, according to a May report from the Congressional Budget Office.

When fully implemented (see Figure 4), central clearing is unlikely to solve the dealer’s current capacity constraints or all of the issues that have given rise to Treasury market dysfunction, such as the fundamental supply/ demand imbalances when there are more sellers than buyers. But it should put the industry more on the hook for its own risks, potentially minimizing the need for the Fed to act as the buyer of last resort in times of stress.

Many experts say that for clearing to be successful, it needs to come along with other measures—some of which the regulators are proposing, like additional trade transparency, and some of which they are still discussing.

Still under debate, for example, is the idea of applying minimum buffers or “haircuts” on Treasury repos, something that regulators are reported to be considering. In this realm, the regulator could require a dealer to collect $101 in collateral on a $100 Treasury repo trade, using the additional collateral to buffer against defaults.

What the Treasury market needs is a backstop of liquidity during times of stress, and it needs to be known on an ex-ante basis that it's available.

An SEC spokeswoman said the agency doesn’t comment on the content of final rulemakings before they are finalized.

FICC is also working with CME Group to enhance a cross-margining arrangement so that netting is possible across outright Treasury trades at FICC and futures at CME Group. Currently, that only covers trades from dealers who are members of both clearinghouses but not their investor clients.

A third idea is having the central bank’s “standing repo” loans available to more market participants, not just primary dealers and banks. In this scenario, any time there was a pullback, a wider range of market participants could put their Treasurys to the Fed and exchange them for cash at a moment’s notice.

“What the Treasury market needs is the backstop of liquidity during times of stress, and it needs to be known on an ex-ante basis that it’s available,” said William C. Dudley, former president of the New York Fed and a senior adviser at Bloomberg Economics. In that scenario, he says, “If that made Treasurys more attractive, the benefits would accrue to the government in the form of lower borrowing costs and traders wouldn’t panic in the first place.”

In and Out

Katy Burne is Editor in Chief of Aerial View and Alta at BNY Mellon, based in New York.