A quiet revolution has been underway in global fixed-income markets over the past 15 years. A significant new asset class, known as private credit, has grown from a fringe product used mainly by medium-sized enterprises and lower-quality borrowers into a multitrillion-dollar market that is administered and controlled by today’s largest asset managers and private equity firms.

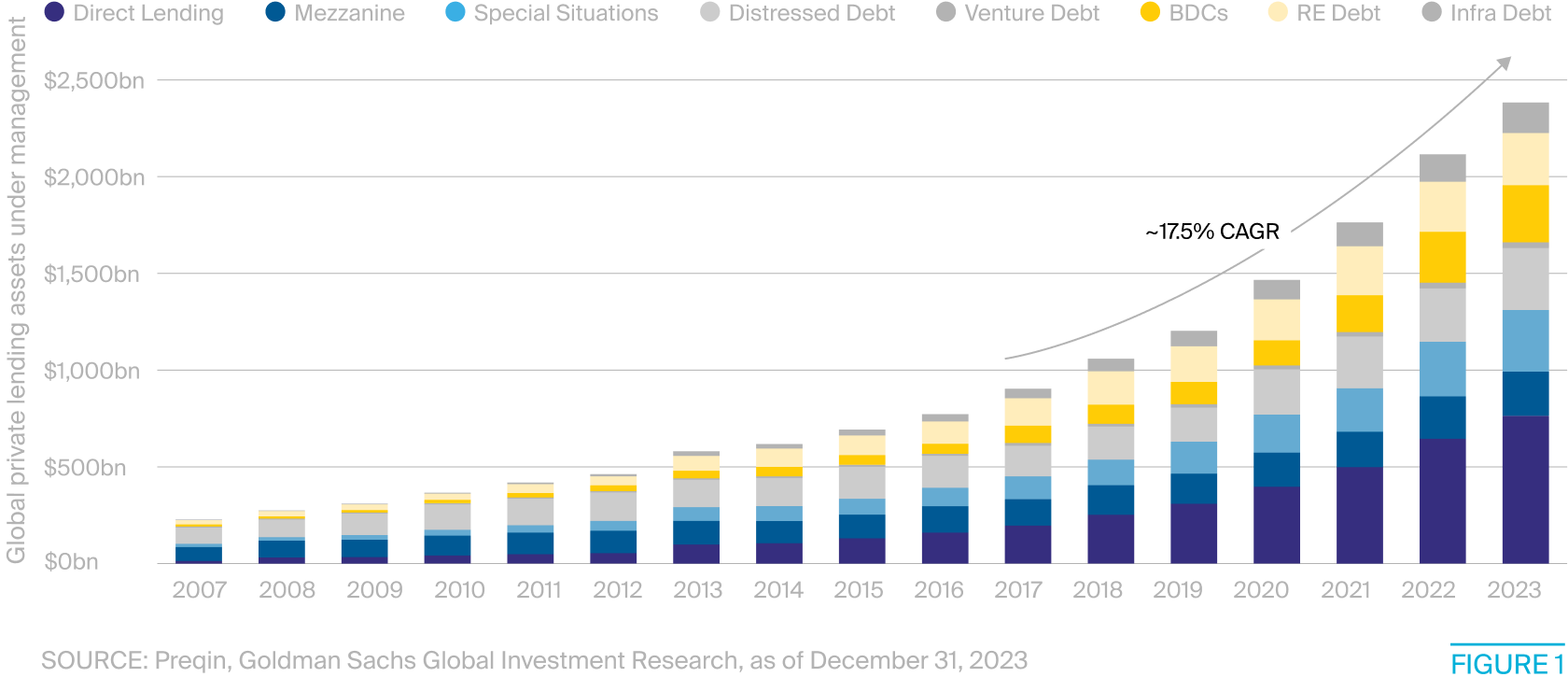

Despite growing more than tenfold since 2007 (see Figure 1), private credit has only recently attracted the attention of the broader investor community and financial regulators. That scrutiny has not — as yet — resulted in these new lenders being caught in the same supervisory net as banks.

But the potential lack of transparency in these loans, the variety in their covenants, and the fact that most of them are floating-rate is causing many to ponder the adverse impact that further fiscal tightening or additional interest rate increases may have on the borrowers and the wider economy.

Explosive Growth

Private credit arrangements are not new in themselves; private placements date back to at least the early 20th century, and private business loans have been issued since time immemorial. It was the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 that helped accelerate the growth of private credit and the post-crisis regulatory changes that followed.

Generally, under those bank supervision rules, the higher the risk weight applied to an asset, the more capital an institution is required to hold against it. These regulations have had a consequent chilling effect on public debt markets, such as syndicated loans. Banks have also become much more discriminating about the clients to which they will lend.

“The big bang came after the Global Financial Crisis, which put the banks on a risk-weighted asset diet and allowed private credit to really take off,” says Louay Mikdashi, head of multi-sector private credit at Neuberger Berman. Recently, the universe of counterparties that are turning to private credit for financing has grown beyond small and credit-impaired borrowers, and the funds themselves have grown much larger.

Young Soo Jang, a researcher specializing in private credit at the Booth School at the University of Chicago, says that one of his studies found 78% of private credit deals are backed by private equity (PE) in the U.S., in part, because regulations like the Federal Reserve’s Leveraged Lending Guidance discourage banks from lending to firms with debt to earnings above a set threshold.

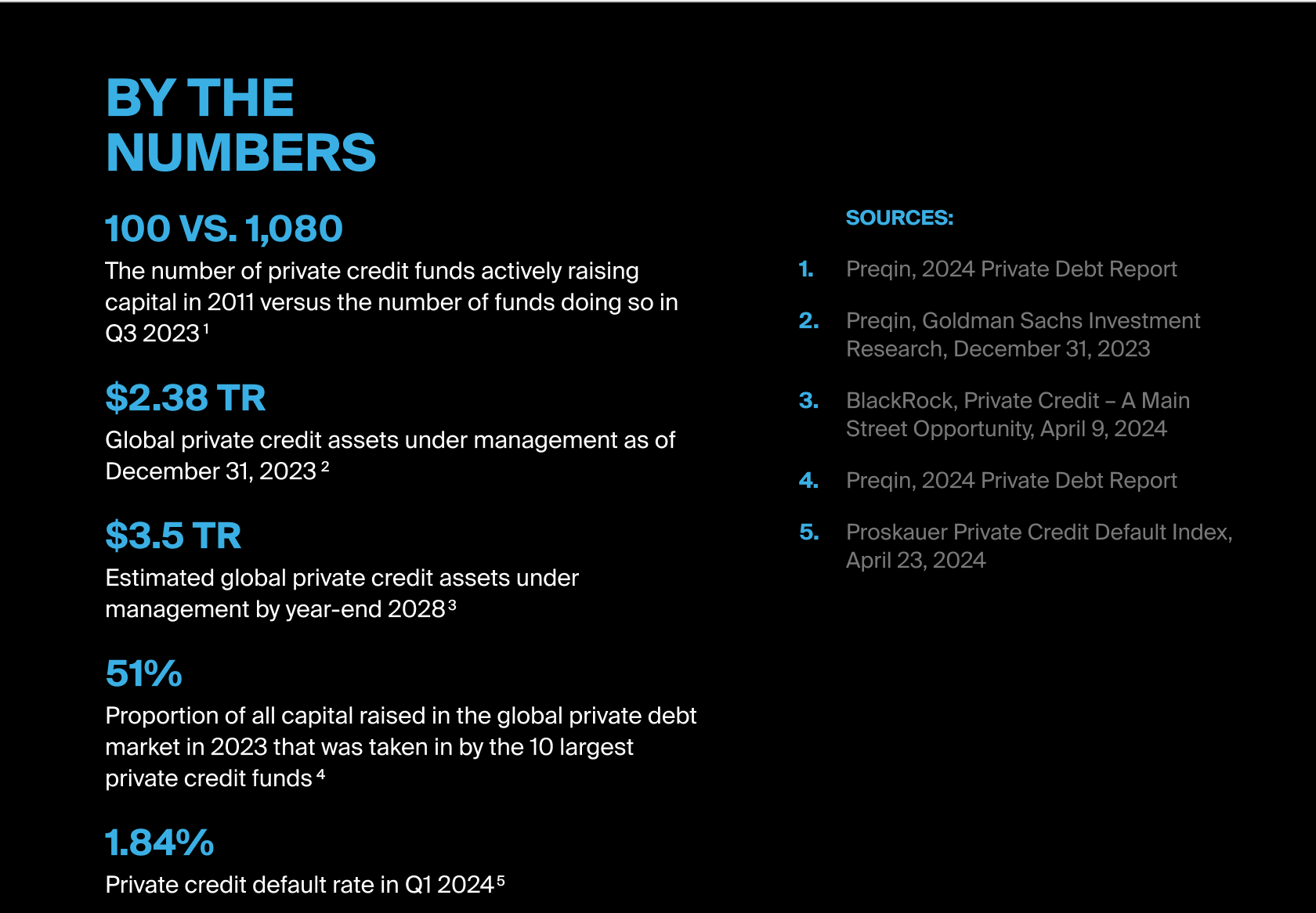

As the amount of private lending has soared, so too has the number of private credit funds actively raising capital. In the third quarter of 2023, there were approximately 1,080 private debt funds in the market globally, up from around 100 in 2011, according to market data provider Preqin.

The firm forecasts that private credit assets under management (AUM) globally will reach $2.8 trillion by the end of 2028. Fund manager BlackRock is even more bullish, suggesting private credit AUM will reach $3.5 trillion by the same year. On the servicing side of the industry, growth in private credit has been equally evident.

Everything Everywhere All At Once

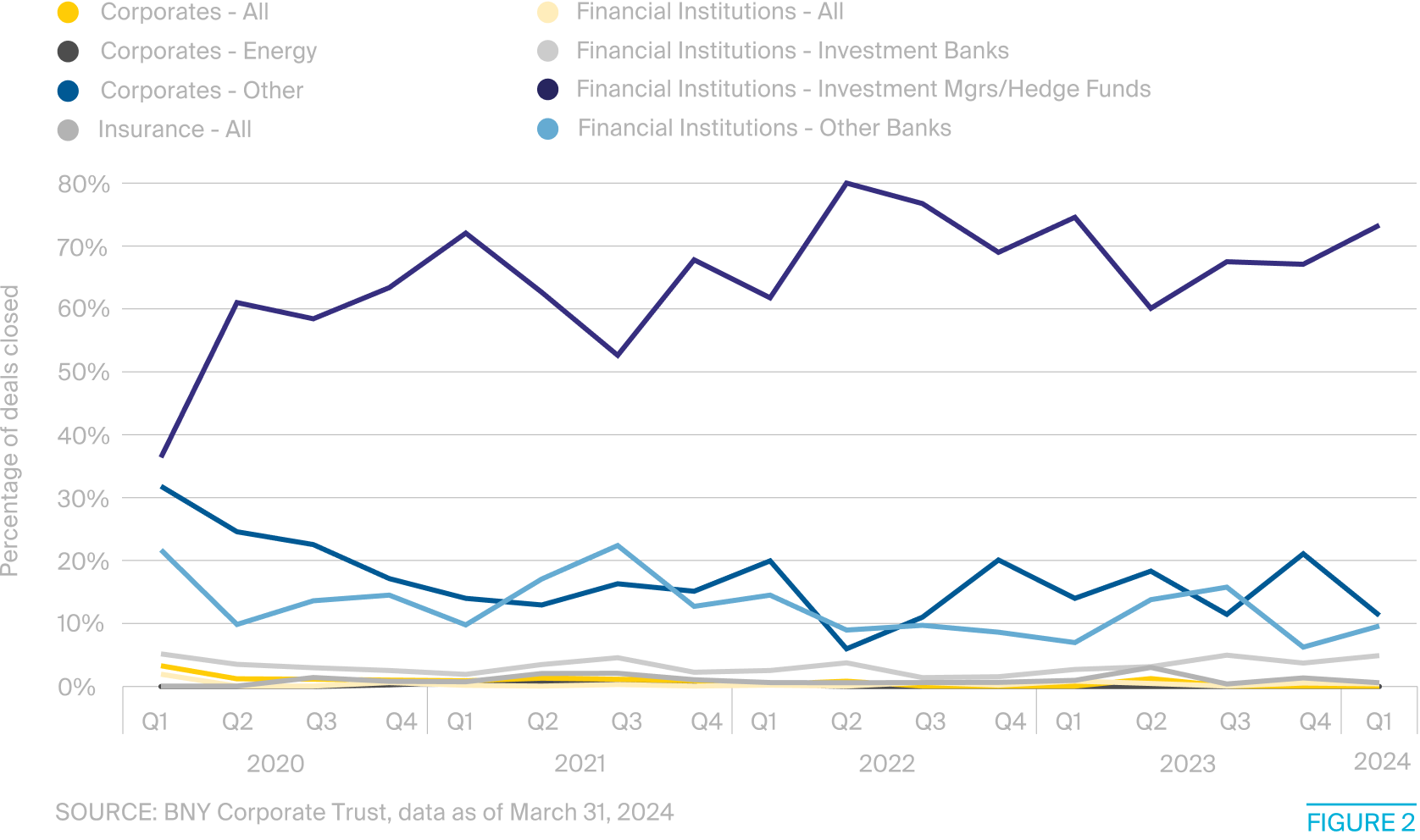

BNY’s Corporate Trust division saw private debt deals account for 65% of its newly added loan servicing mandates last year, up from 40% in 2021. The vast majority of loan deals serviced by the team now come from deal appointments from investment managers rather than banks, and those firms’ share of deal flow on the corporate trust platform has grown to 73% as of March 31 this year from 36% four years ago (see Figure 2).

Not content with the already breakneck pace of a sector that is experiencing compound annual growth rates of 17.5%, many PE firms acting as general partners for private credit funds have been busy acquiring life insurers as new sources of capital, motivated by their hoards of cash, cash equivalents, government securities and other liquid assets.

The illiquidity premium — coupled with a PE firm’s origination capabilities — can allow investors a pickup of as much as 250bps above an equivalent investment-grade risk.

This sequence includes the January 2022 acquisition of retirement company Athene by alternatives manager Apollo, the November 2023 completion of KKR’s acquisition of insurer Global Atlantic, and the September 2023 creation of Blackstone Credit & Insurance, combining the PE firm’s corporate credit, asset-based finance and insurance groups into a single unit.

The long-dated nature of insurance and retirement liabilities aligns well with the lengthy lock-up periods imposed by private debt funds, but reallocating insurance assets into the world of private credit requires some financial engineering.

“The intersection of credit and insurance has been ramping up for the past five years via acquisitions, strategic partnerships and larger allocations into the space,” says Dan Tennant, head of alternatives at BNY's Global Client Management group. “The illiquidity premium — coupled with a PE firm’s origination capabilities — can allow investors a pickup of as much as 250bps above an equivalent investment-grade risk.”

Private Credit: An Explainer

Private credit is a fast-growing market in which borrowers access capital not through the traditional bank-intermediated avenues of syndicated loans, corporate bonds, or commercial and industrial loans, but via privately negotiated loans arranged by a private credit fund sponsor.

A typical private credit transaction works as follows: A fund manager — usually a private equity (PE) firm (often called a financial sponsor), asset manager or alternatives manager — establishes a private credit fund. The fund aims to raise a pool of capital to deploy in a specific fixed-income opportunity, such as distressed debt.

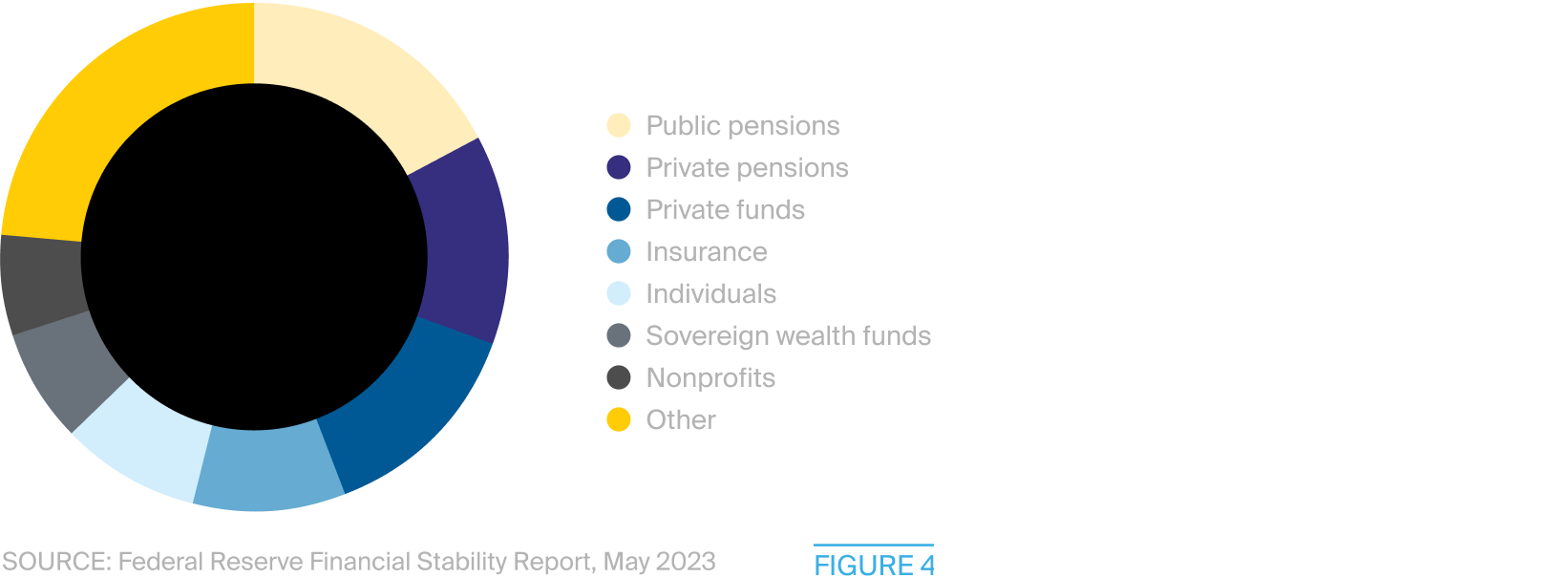

The fund manager — often referred to using the PE term “general partner” (GP) — seeks to raise a set amount of capital for the fund from investors referred to as limited partners (LPs – see Figure 4). Once the fund is fully subscribed, the GP establishes the terms of the loan with the borrower and provides funding.

Private credit is extended at a floating interest rate (in the U.S., usually the Secured Overnight Financing Rate plus a spread of several hundred basis points) for a fixed term, often five or 10 years.

The borrowers of private credit have traditionally been middle-market companies and corporate names with a credit rating of B-minus or lower. This community uses the funding because, although it is more expensive than that available in the public markets, it has the advantage of facing a single creditor, as well as fewer obligations and restrictions relative to the public debt markets.

Retail Shopping

In tandem with acquiring institutional asset owners as a source of dry powder, fund managers have also set their sights on the humble retail investor to help grow their funds. Traditionally, retail investors have not been able to access the world of private credit because consumer protections generally restrict the types of investment options available to individuals.

A New Look For Lending

This is beginning to change, however. U.S. retail investors are now able to gain some exposure to private credit through vehicles known as business development companies (BDCs), which are funds designed to allow small and midsize companies to access capital pools that would otherwise be off-limits.

Outside of the U.S., there has also been increased growth of European Long-Term Investment Funds (ELTIFs) that act similarly, with new possibilities opening up as the European Union’s new ELTIF reforms took effect in January 2024. As a result of these changes, private markets that have previously been the preserve of professional investors will now be broadly accessible for retail investment in Europe.

“We are seeing growth in all dimensions: geographical expansion, new types of lenders, new types of collateral, and in credit quality as we begin to see private credit moving into the investment-grade space,” says Jiri Krol, deputy CEO of the Alternative Investment Management Association.

BDCs come in three flavors: private BDCs, which are similar to PE funds, have a fixed term and are frequently subject to capital calls; non-listed BDCs, which do not trade on an exchange but are offered on a continuous basis and may utilize capital calls; and exchange-traded BDCs, which are listed and have no capital calls. The potential liquidity mismatch the BDC structure can introduce in private market instruments was starkly demonstrated in 2022, when Blackstone disclosed in a regulatory filing that investor redemption requests from its BCRED Private Credit Fund had hit 5%, the preset limit at which further withdrawals could be restricted. Blackstone elected not to impose redemption restrictions and investors were able to withdraw funds freely, but the episode illustrated the potential for liquidity stresses to develop when a fund invested in long-term illiquid credit is made available to skittish retail investors.

“Registered investment advisors struggle with the paperwork, with getting their clients into these vehicles and with education about alternatives, which is a huge barrier to overcome,” explains Chris Vella, chief investment officer for investor solutions at BNY Investments.

Risky Business?

As the private credit market expands, provides funding to an ever-larger community of borrowers and seeks more participation by retail investors, policymakers are beginning to pay attention.

The loan covenants embedded within private credit structures has been one area of focus — in particular, “covenant-lite” lending arrangements. A February research paper from the Federal Reserve observed, “Since private credit managers have a mandate to deliver high returns within a fixed timeframe, fund managers might choose riskier deals, offer more covenant-lite loans, or more generally reduce underwriting standards as opportunities dry up when the economy slows down.”

Some private credit experts counter this, noting that overall default rates in private credit compare favorably to those of broadly syndicated loans and high-yield bonds, and more importantly, recovery rate projections remain high. They also point to how private loans can have numerous features to compel fiscal probity, including maintenance covenants, which would trigger before an actual default.

Another potential concern is the lack of transparency surrounding the structures themselves. In November 2023, Sherrod Brown, Chairman of the U.S. Senate Banking Committee, sent a letter to the U.S. financial regulatory agencies observing that “private credit funds operate in the shadows … in the absence of sufficient oversight and accountability.”

In its December 2023 Annual Report, the U.S. Financial Stability Oversight Council recommended that its member agencies continue to monitor levels of nonfinancial business leverage, trends in asset valuations and the ability of the financial sector to manage severe simultaneous losses.

The Winner Takes it All (Almost)

In Good Company

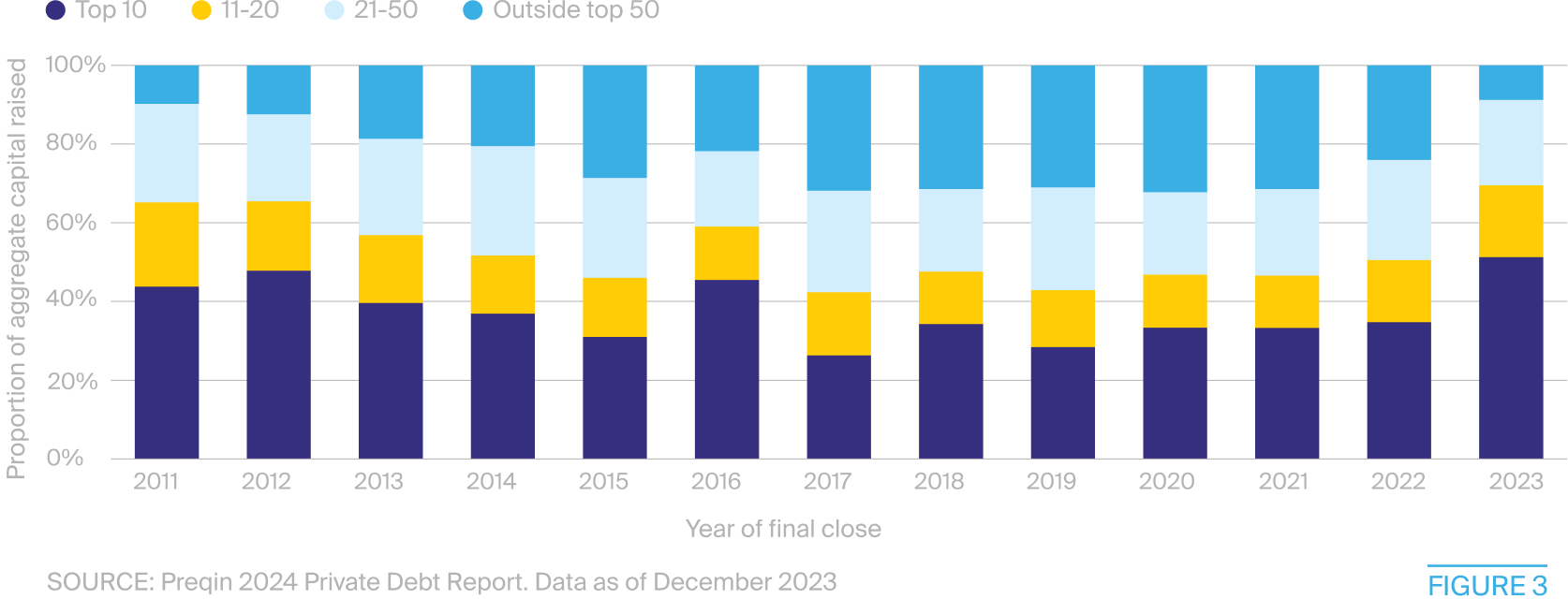

One potential financial stability issue is concentration risk among the largest private credit fund managers. As of 2023, the 10 largest private credit funds accounted for 51% of all the capital raised in the global private debt market, up from 35% in 2022. The top 50 funds account for 91% of all the private capital raised last year, compared to 76% in 2022 (see Figure 3).

Some worry about how resilient floating-rate private loans will prove to be in the face of sustained elevated interest rates, especially since Fed rate cuts are now not expected until the end of 2024, if at all this year.

Scenario analysis conducted by S&P Global in December 2023 concluded that even a moderate stress, such as the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) rising 1% from current rates, together with a 20% fall in EBITDA, could leave 28% of B-minus-rated private credit borrowers at risk of a downgrade. This suggests further rate hikes could inflict considerable stress on borrowers.

We’ve been in a higher interest rate environment for a while now, and we are yet to see those rates having an observable effect on private credit borrower defaults.

Others say there is scant evidence of stresses appearing thus far. The fact that U.S. interest rates were raised 11 times in just 17 months and have remained higher for longer than many had expected has not yet translated into a meaningful uptick in defaults among private credit borrowers.

“We’ve been in a higher interest rate environment for a while now, and we are yet to see those rates having an observable effect on private credit borrower defaults,” explains Jessica Shearer, a partner in Proskauer Rose’s credit group. A private credit default index maintained by the law firm recorded an overall default rate of just 1.84% in the first quarter of 2024, down from 2.15% in the first quarter of 2023.

Analysis by the Fed published in May 2023 found that the financial stability risks posed by private credit are “limited” due to the fact that the assets are mostly illiquid, the funds use a closed-end structure that locks up investor capital for five to 10 years, and the funds typically use little leverage.

The Fed did, however, warn that private credit funds can pose liquidity risks for their investors in the form of capital calls, typically giving limited partners 10 days to provide capital when demanded, and that the private credit sector remains opaque, making it difficult to assess the default risk in private credit portfolios.

We live in a world where — based upon liquidity, price, terms, and availability of capital — debt issuers have the ability to go back and forth between the public loan market and private credit.

Conclusion

The trajectory for private credit over the remainder of this decade seems all but assured. As the market continues to draw in more investors — both institutional and retail — and expands its borrower base from the middle market to the very largest corporate entities, there seems to be little on the horizon, absent regulatory intervention, that will slow its further expansion.

While that explosive growth will only continue to draw concerns regarding the minimal indirect regulation of this activity, it appears at present that private credit is set to become even more entrenched as an established alternative to loans, bonds and other public debt.

“We live in a world now where — based upon liquidity, price, terms, and availability of capital — debt issuers have the ability to go back and forth between the public loan market and private credit,” concludes Steve Vaccaro, CEO of CIFC Asset Management. “One is not going to replace the other, but the differences between the two are likely to narrow as public and private credit compete for the same deals and [as] the market arbitrages away a lot of their respective differences over time.”